by Debora Rafeld – Zilberstein Ha’aretz books 19.8.1998

by Yosepha Michaeli. Independent Publishing, pg 266

In one encounter between my body and myself, which was sponsored by the “Body Cognition Method,” years of firmly fixed animosity towards anything that may resemble a physical education class has come to an end. Since the publication of this book I have been presenting it as someone who has literally experienced on her own body the blessed results of the lessons.

Yosepha Michaeli, the author of the book, is a physiotherapist who has been developing lessons in movement for about 40 years. The Book provides 9 sample movement lessons, orthopedically analyzed and explained, allowing anyone seeking to improve his/her posture, health and esthetics to peek into the unique workshop led by Michaeli and teacher-students she has trained during years of research, development and imparting the Body Cognition Method.

In this book, Michaeli does not preach her doctrine in an orderly fashion, but in the in-depth analysis of the lessons and the explanations accompanying each exercise provided, some of the method’s principles are revealed, along with the vast knowledge and fresh biomechanical concept the Body Cognition Method has established.

Unlike Yoga or Tai Chi, the Body Cognition Method is not based on certain regular acquired exercises, but on non-repetitive movement exercises and diverse positions and different organization of the physical postures, which joined together, form an almost choreographic continuity with a characteristic structure distinguishing each lesson.

This allows endless variety, and the physical attention the lesson requires enables the experience of the physical subtleties stemming from refined movements which develop with time. Even if a movement is repeated in the different lessons, the new context in which the movement is set gives it new qualities and characteristics.

The name of the method implies the key role which the pupil’s consciousness plays in the optimal organization of the physical posture these movement lessons are “educating” towards. The lessons in the Body Cognition encourage the pupils to investigate the depth of the body movement and improve it. The entire lesson is composed in such a way that it “stimulates” the pupils to understand through their senses the process of producing a movement/posture in all of its phases. Our automatic movement patterns are “invited” during the lesson to undergo a controlled inspection and correction, with constant emphasis on the quality of execution, on the in-tuned “connection” of the pupil to his/her unique

body with its limitations and tendencies, and to the reactions the movement provokes.

The lesson usually begins and ends in a standing position, also used as a gentle “transition ritual” from the common movement reality to the intrinsic movement of the lesson, and in the end it helps the body to organize what was absorbed in the lesson for use in everyday life. The first lesson, is just a common posture position, but in the context of the lesson and in the brief comments made by the instructor it is not inferior to the lessons that follow. It demands an astonishing, contemplative attention, on its physical presence in this position which is taken for granted outside of the studio.

Using very few words the instructor reminds the pupils to examine their limbs while standing: how far apart are the feet, are they parallel to one another, are the knees straight and to what extent, is the weight placed on the legs equally? And the sole of the foot itself, the one carrying the entire weight of the body – is the burden of the weight on it divided in a “fair” manner, or is it carrying most of the weight, or maybe it’s the other way around, with most of the weight placed on the heel? What is the consequence of each of these options for the quality of the “erection” of the entire body? Is the arch of the feet maintained? Or is pressure being placed on the inner part of the soles? And the toes – are they pushed against each other, or spread apart?

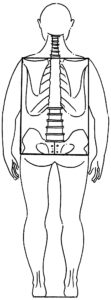

And the knees above the feet – do they tend to point towards each other, or do they point entirely to the sides? Do they tend to lock when straight, or can they be straightened while remaining springy? And how do the hip joints react when standing, what is required of them, how do they come into play? How will we know without a mirror if we are correctly aligned on the symmetrical axis? How do we organize lower back and hip vertebrae? Whether and how they try to join the vertical structure we are building above the pelvis? How should we refer to the lower curve of the spine? Are we exaggerating it and creating unnecessary pressure on some of the vertebrae? Is each vertebra receiving the space and air it deserves? Can we feel from within us, in the vertebrae’s structure of the spine, or are the vertebrae unwilling to move but in “clusters” and as one unit?

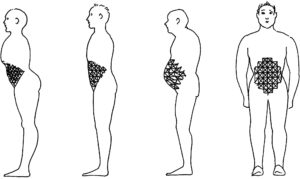

The abdomen muscles should work in a standing position so that we may reach an optimal erectness and symmetry. But to what extent? Is the strain placed on them too much? When we attempt to reduce the strain do we relax too much, thus straining the back? How do we correctly divide the strain between the abdominal muscles and the back and buttocks muscles? And what do we do with our hands when they are not in use? Is the elbow joint completely straight? Do the hands know how to rest when no effort is required of them? And the palm of the hand – is it clenched? Is it unfurled? Are the fingers touching each other? Are they resting on the thighs or hanging to their sides?

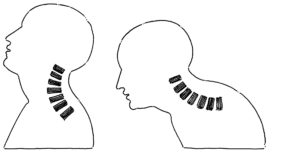

And what is the position of the chin – the bottom part of the heavy head ball towering on top the body tower – is the link between the chin’s position

to the neck’s vertebrae clear to us today? Are we aware that when we thrust it upwards we “shorten” the nape, and press the neck’s vertebrae against each other? And what about the shoulders? Are they spread to the sides or slightly slouched forwards? Are they aligned? And what is going on with the shoulder blades in the back? How do they respond to changes in the shoulders? How far out do they protrude, to what extend do they correspond with each other? It seems they can be lowered and raised, arched or concaved. It is not simple, you must examine, contemplate, especially since both the spine and the thorax tend to interact.

At the beginning and the end of a lesson, the simple standing position is reevaluated. In the Body Cognition studio there are no mirrors. The pupils must learn to experience their posture by paying attention to the relationship they set between their body parts, relying on their sense of proprioception (the sense informing a person of the relative position of neighboring parts of the body), demanding more and more information, developing precision. In his senses, the pupil discovers the link between the body parts; on the one hand a body part has an autonomic moving space, and on the other hand it is affected by and influences the position of the other body parts. It is important to know how to isolate as well as how to connect.

People do not like to stand. Most find it more comfortable to walk, and of course sit. But only few can explain where and how the difficulties are expressed in the body. Is it hard on the legs, the waist, the upper back, the nape? Which body part is being strained? Is there one answer for all? What is unique to the personal body and what is universal and general? Nothing is taken for granted. In each lesson one learns to stand again, to distinguish between the different qualities of the experience, and to enter the kind of attentiveness the different exercises call for.

With no machines, on a mat or mattress (for those who find it hard), and no mirror, each of the pupils employs a personal body treatment. They listen to the instructions and try to implement them. In most cases, the instructor does not demonstrate the movement in order to prevent an automatic implementation, thus compelling the cognitive system to take an active part in producing the movement. The pace of the exercise is also not dictated by the instructor or by music. A general instruction is given to work slowly. That is it. Each of the pupils must gradually discover his own personal qualitative pace, self direct throughout the special experience of the slowing down marvel.

When we find a certain exercise “difficult,” what is the reason for it? Is it because we fail to understand what is required, and therefore do not know what to demand of our body, or is the body resisting? And what then? Should we oppose the resistance or “accept” it? Should we give in to our body? Should we respect it enough to demand of it, but “gradually” and not forcefully? Are we able to negotiate intelligibly with a joint refusing to reach the desired range? When is giving in the correct thing to do, and to what extent? Only you can know the answer, if you are in-tuned.

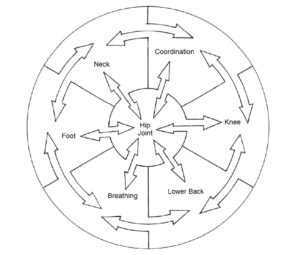

Even though each lesson focuses on a specific body part, the entire body is treated throughout the lesson. The link between the specific body part to the rest of the body will be studied and examined in different variations during the lesson. Holism is not only a motto here. The relation between the different body parts is inherent to the movement experience; it is the syntax of the learned movement language. The suggestion to “think the movement” is also, in fact a consistent attempt to cancel the Cartesian separation between the “self” and “the body”, to experience the movement, the sensation, the intent and the control as additional dimensions of the very same thing.

I hope this book will be adopted by the physical education teachers in schools, and that with its guidance they will succeed in turning the physical education classes into a “self” broadening experience for the students, which teaches through the body and the senses that the “how” is just as important as the “what,” that the road to the “self” does not bypass the body, but includes it. That awareness and understanding of the movemen of the body is a central stage in the development of our ability to know ourselves. And that is the starting point of wisdom.